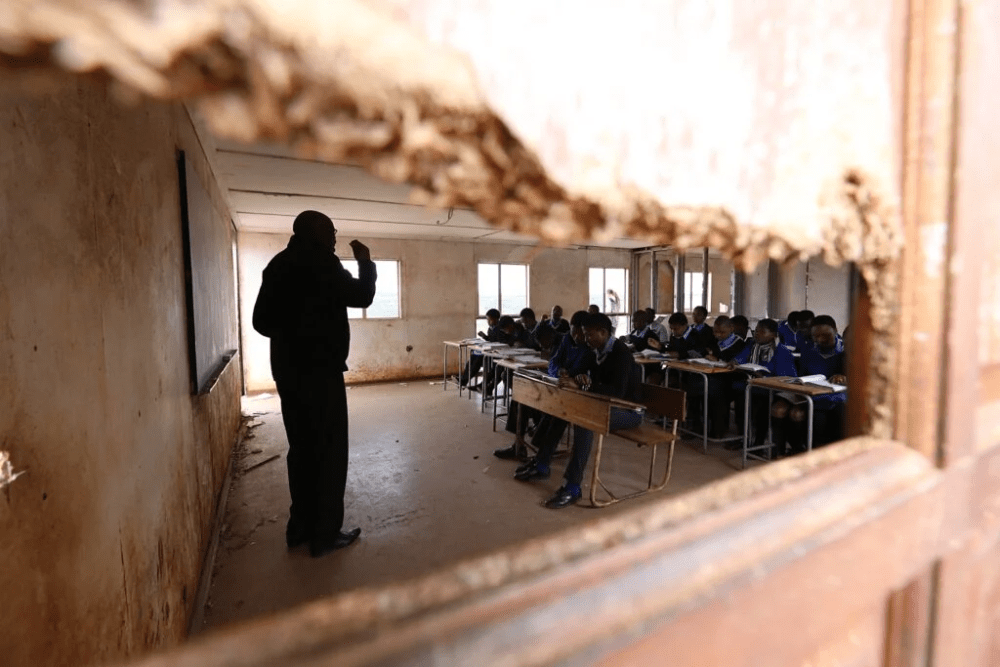

South Africa has a large public sector wage bill, but education is one of the fields that must be prioritised. (Photo by Gallo Images / Sunday Times / Thuli Dlamini)

“The wait to find out how many teachers at my school will be cut has been stressful as I started my new job as a first-time teacher in March 2024 and now having these WCED [Western Cape Education Department] teacher cuts hanging over my head hasn’t been easy.

“I fear for my learners that they won’t get the attention they need in an environment where there will be close to 60 learners in a class.”

In the past few months, many teachers in their first year of teaching have received letters terminating their contracts after the WCED’s decision to cut over 2 400 teacher contracts by the end of this year.

These cuts directly affect newly-qualified teachers (NQTs), who are increasingly employed in contract positions. NQTs like Gaby*, quoted above, are living in a state of heightened anxiety as they expect to receive similar letters.

This article highlights the experience of NQTs who are deeply concerned about the impact these austerity measures will have on their learners and their own working conditions and livelihoods.

They are involved in the Newly Qualified Teachers’ Project (a joint initiative of the University of Cape Town and Cape Peninsula University of Technology, which is supported by the HCI Foundation, the Saville Foundation, UCT and CPUT) that provides support and mentorship as they embark on their professional journeys in education. They are committed, resilient and eager to learn, bringing all of their energy, resourcefulness, passion and innovation to schools.

For over a decade, fiscal austerity has had a damaging impact on education, particularly in under-resourced schools in poor and working-class communities. In our work with NQTs since 2016, we have seen the immense expectations and responsibilities placed on teachers from their first day in the classroom.

They are starting their careers in a context of injustice where they grapple daily with the legacies of a racialised and deeply unequal education system. These cuts will place an additional burden on NQTs who are still finding their feet, with very little institutional support.

There are hundreds of NQTs who are eager to make meaningful contributions in our schools.They are sorely needed with an ageing teacher demographic heading toward retirement. According to the Supply and Demand ReportSouth African public education needs “exceptionally large number of joiners” and a doubling in “the annual production of grade one to 12 teachers […] from the current level of around 30 540 to a level of 59 034 by 2030”. Yet, approximately a third of this year’s cohort from the NQT Project, who expected to start their teaching careers, have been unable to find work.

Some teachers employed on short-term contracts have already lost their jobs, based on the “last in, first out” approach. Other contract teachers were hired with the promise of conversion to a permanent post.

The WCED claims not to be firing teachers, however, these measures mean that many teachers are in effect losing their jobs and the promise of permanent employment. High levels of staff turnover are known to inhibit teaching and learning, the efficacy and stability of schools and efforts to redress the legacies of apartheid.

Classroom realities and overcrowding

The consequences of these cuts are best understood through the NQTs’ own descriptions of their experiences teaching in under-resourced schools.

Since qualifying with a Postgraduate Certificate in Education, Tatum has worked at a school on the Cape Flats. In addition to English and history, she was asked to teach two subjects she had not studied and was responsible for all the assessment and administration of one of those subjects.

“The decision to cut teaching jobs will have devastating effects on both educators and learners. It will negatively impact learners, especially in under-resourced schools, leaving many classrooms overcrowded and reducing the quality of education,” she says.

Themba has also struggled with teaching large classes at another school on the Cape Flats where pupils are affected by gang violence. In his first year of teaching, he has been the only isiXhosa teacher for the entire school, as well as head of department.

After a very challenging start, Themba has motivated his learners to be active and engaged in his class and earned their respect.

“Each grade 12 class has around 40 learners, which makes it nearly impossible to offer targeted interventions for those at risk. Managing these class sizes, along with my other teaching duties, leaves little room for individualised support. I believe every learner deserves a quality education,” he says.

When the proposed teacher cuts are implemented, already large class sizes will be untenable. At the moment, too many pupils do not receive the academic and psycho-social support they need. Very few schools have resources for any kind of differentiated learning. With even bigger classes, more learners will struggle alone and fail.

The difficulty of short-term contracts

Reese chose education as a career after many years of working in other industries. He teaches 13 classes and many of his learners struggle with substance abuse, lack of motivation and are repeating their grade.

Reese has endured a year of job insecurity, with his contract terminated at the end of the first term, and then reinstated on the first day of the second term. The challenging environment and stress caused by the lack of a permanent contract has caused him to be sick several times.

“It was heartbreaking thinking how a contract for a year could be torn up and thrown away just like that. It caused deep anxiety and worry. Then came the news of more job cuts and that many teachers would not have a job.

“I was deadly concerned as I went through this before. The fact that we are losing posts makes no sense … This will cause tremendous strain on our already fragile and fatigued mental state.”

Many NQTs are hired on short-term contracts, which is destabilising for a new teacher because it does not give them time to become familiar with the full cycle of assessments, annual teaching plans and other events in an academic year. It is also difficult for teachers to form relationships with learners, which are the foundation of effective teaching and learning.

Teachers as breadwinners

Gaby, who has always viewed teaching as a “calling”, started working in March. She is qualified to teach English and geography, but she is teaching other subjects she has never studied. She sits on various staff committees and runs Saturday classes for those who would like extra lessons.

“Finally earning a decent salary has given me the ability to help my mother financially. Not having my job from 31 December 2024 will be heavy on not only my shoulders but on hers too.”

Anele wanted to be in a profession where she would make a difference and studying for her postgraduate education certificate gave this passion a focus. She was hired on a 6-month contract, which was terminated after three, then she was rehired one month into the second term.

“As the breadwinner, losing my job means I will struggle to cover essential expenses, including my daughter’s school fees. The uncertainty of being unable to provide for her education is heartbreaking.

“Also, without a steady income, I will be forced to leave the Western Cape and return to the Eastern Cape, as I won’t be able to afford rent. This disruption is not only financially challenging but emotionally difficult, as it means uprooting my life and starting over.”

Themba also spoke about the emotional toll of the situation.

“After many years of hard work and dedication, the prospect of finally earning a stable income is no longer just a dream but a long-awaited reality — one that my mother has prayed for. The most devastating part is that I now face the reality of not having a job. This heartbreaking situation weighs on me every day, as I struggle with how to share this news with her.”

Like many teachers, Gaby, Anele and Themba are concerned by the contract cuts, which affect not only themselves, but their families and dependents. They went into the year with the promise of permanent employment, instead they live with the uncertainty of not knowing whether they will have a job next year.

Leaving the profession

As an NQT, Crystal is the only history teacher at her school and is the head of subject. There has been a different history teacher every year for the last five years. Her learners are demotivated and took months to trust that she will stay.

Many are dealing with substance abuse and some are parents themselves. Crystal has focused on forming relationships with her classes, and runs extra afternoon and Saturday classes for her grade 12s.

“I’m very, very afraid of what my school is going to look like next year. We have 20 teachers and we are a school of about 500 learners. And this is already a school dealing with a lot. They let go of three contract teachers, so just 17 remain.

“I teach all classes from grade nine through 12 without a senior teacher. There’s a teacher who used to teach grade eight for me and she was let go, which means that next year I’m going to have to take Grade eight to 12. I’m actually reconsidering whether the profession is still for me with all the added pressure.”

Crystal is very worried about the effect of the cuts on pupils because the constant churn of staff has resulted in them not trusting teachers and, in turn, not being interested in those subjects.

As her timetable is full, she doesn’t know how she will add more classes to her weekly schedule. After just one year in the job, Crystal is considering leaving the profession. She is like many NQTs who have worked hard to gain their teaching qualifications and who were excited to get into the classroom.

Much time, money and energy has gone into training new teachers. With the cuts and lack of job security, new teachers are leaving the profession and, in many cases, the country.

How can we possibly deliver quality education with fewer teachers in the system? These newly qualified teachers are the next generation of leaders in education. They go over and above their already demanding jobs to help their learners and involve them in activities beyond the curriculum.

These austerity measures will have devastating effects on teachers but the greater impact will be on hundreds and thousands of schoolchildren. In Tatum’s words, “Cutting education is cutting the future and will have a long-lasting and profound impact.”

*Pseudonyms have been used for all the teachers

Judy Sacks, Hannah Carrim, Professor Rochelle Kapp, Dr Kate Angier and Melanie Sadeck are teacher educators and are part of the management team of the Newly Qualified Teachers’ Project. Luthando Tetani and Zimasa Ntontela are graduates of the Newly Qualified Teachers’ Project 2024. They teach at schools in Cape Town. They all write in their personal capacities.