In “Living in Low Places ,” Hu takes readers on a more personal journey, diving deeper into his inner world. He explores how his childhood and family shaped his personality, how he navigates life as an “ordinary” person, how his bond with literature grew, and how he eventually found inner peace. Reflecting on his life, Hu describes realizing how the “elsewhere” moments and “instances of surprise in the ordinary” have not only helped him endure his life’s hardships but also guided him toward his calling as a writer. The following is the preface from “Living in Low Places,” titled “Ordinary Things”:

In 2016, there was a period when I temporarily lived in a friend’s factory dormitory. One day, he told me that his dormmates had noticed I spent every evening reading books. He expressed surprise at my studiousness. His use of the word “studious” startled me for a moment — at 37, I hadn’t heard that word in years. I later realized — not just from this single incident, of course, but from my overall understanding of him — that for my friend, reading was about self-improvement, acquiring skills, and gaining knowledge to improve one’s life. Any reading that did not meet these goals was, in his view, a waste of time.

However, I didn’t know how to apply what I had learned from reading novels like “Madame Bovary,” “The Brothers Karamazov,” “Anna Karenina,” “The Castle,” or “In Search of Lost Time” in a practical way. Fortunately, he didn’t know what I was reading; if he had, he would have been disappointed and worried, believing I was wasting my time.

At that time, I had just finished reading a few books he had recommended to me, all related to entrepreneurship and tech thinking, as we were business partners. Perhaps he thought I was continuing my studies in the dormitory every night to lay a solid foundation for our venture. But the truth was, I had been reading Charles Bukowski. I remember this clearly because at the time, it seemed almost ironic to describe reading Bukowski as being “studious” — what could I possibly learn from him? How to be cynical and indifferent, or to recklessly mess everything up?

I read Bukowski simply because I enjoyed it. I’ve long understood that literature doesn’t help me gain other things. For instance, it won’t help me find a job. Of course, I don’t need literature to find me a job. Literature only brings me into its own world, which is exactly what I want. But I can’t blame my friend for his views on reading; he sees it as a means to an end and mainly reads reference books, so it makes sense that he would focus on its “usefulness.”

As for whether literature is — or even should be — useful, there is an oft-repeated quote from Zhuangzi (the 4th century BC philosopher): “All men know the advantage of being useful, but no one knows the advantage of being useless.” This summarizing statement appears at the end of “Ways of the Human World,” a section of “Inner Chapters” in “Zhuangzi.” In the original text, the meaning is relatively clear: Zhuangzi believed that in a chaotic world, those with talent and ambition are easily manipulated by those in power and may even become sacrificial lambs. In contrast, those without talent or ambition, or those with physical disabilities, are more likely to be sheltered from harm. However, when people quote this saying today, they often do so out of context, making its connotations broader and more ambiguous.

My relationship with reading and writing was somewhat similar, or at least until 2020. Before then, my writing was almost unknown and had brought me no financial return. The changes after 2020, I attribute to opportunity and luck; a chance fell into my lap, and I happened to catch it. I didn’t plan for success or strive to achieve it. I started writing in 2009. In the early years, although I did submit my work to publications in the hopes of being published, publication was never my main goal. For me, writing was first and foremost an exercise in personal expression, an aesthetic way to approach life. It was nice if my work got published, but I wouldn’t change my writing just to achieve that.

After “Beijing Courier ” was published, I was often asked if I would pursue a writing-related job in the future. I hadn’t considered this because, with my resume, education, and age, it seemed impossible. But once the question had been raised, I had to give it serious thought. I’m not opposed to the idea of making money through writing — for instance, by taking on a writing job — but I am particular about content. Professional writing cannot represent who I am. I still need to maintain my personal writing outside of work because that is what truly matters to me. What I pursue is the act of writing itself, not something external to it. I believe art — I mean art in the narrow sense — is about the intangible. Art is not a tool or a method to achieve something — it is an end in itself.

In this collection, the first chapter includes three pieces about my childhood and family. Looking back, I realize that school mainly taught me knowledge and discipline, while the cultivation of ideas was often hollow and had little impact on me. The saying “example teaches better than precept” holds true; in fact, the influence of my family was more decisive than my school education. How my parents viewed life and society, what they believed and followed, and how they expressed their feelings toward me played a larger role in shaping my character, temperament, and aspirations, which, combined with my later social experiences, collectively molded who I am today. This chapter is also a continuation of the autobiographical writing from “Beijing Courier.”

The second chapter, “Why I Write,” reflects on my writing journey and explores how writing has helped me understand life and myself. For me, writing is both a way to process and savor life, and a way to deeply reflect on who I am. In my experience, life and reading provide the raw material through which I observe myself and clarify my identity. Initially, my writing was a way to project these observations and insights in various forms. Over time, it evolved into a process of transcending from self to non-self. This journey of self-discovery through writing is likely to last a lifetime, which is why I will never stop writing.

The third chapter contains essays documenting my everyday observations and thoughts. These pieces are byproducts of my novel-writing process and can be seen as exercises in honing my language skills. However, I prefer to view all my writing up to this point — not just these informal essays — as practice. I’ve never felt that my writing is sufficiently polished or mature. In fact, I enjoy this “immaturity” in my writing: it suggests open-ended possibilities. I hope to approach writing with this practice mindset throughout my life.

The content of these essays is decidedly mundane, detailing experiences like waking up in my rented flat in the early morning, reflecting on a photo of myself, watching ants hunt earthworms, or getting a haircut in a barbershop one day, and then again on another day. Some essays are narrative, some emotional or contemplative, and some might just be my grumblings. Regardless of their nature, they hold no practical value. They do not teach, solve problems, or offer new knowledge or profound insights. Literature, like philosophy, cannot be directly applied to reality and be expected to solve real-life problems — if it could, it would be terribly inefficient. Yet literature can influence people in ways that, while not immediate or tangible, can be fundamental and profound.

A quote from Raymond Carver has always resonated with me: “At the risk of appearing foolish, a writer sometimes needs to be able to just stand and gape at this or that thing — a sunset or an old shoe — in absolute and simple amazement.” To me, literature is not about conveying information to the reader, but about touching something within them. Unique things often have specific characteristics, implications, interests, or intentions that distance them from the essential and universal nature of things. Art’s imagery, I believe, is naturally closer to ordinary things, which is why “ordinary things” are the fertile ground I cultivate in my writing.

Like most people, I am just an ordinary person. At least until I turned 40, I worked unremarkable jobs and earned below-average wages. No one ever described me as “outstanding,” and few, if any, truly cared about my inner world. I am not the stone marker atop a mountain indicating its height; I’m a small, unremarkable pebble at its base, indistinguishable from countless others. In a sense, everything in this book comes from the gifts of living in these low places.

This article, translated by Carrie Davies, is an excerpt from Hu Anyan’s book “Living in Low Places,” published by Insight Media in August 2024. It is republished here with permission.

Editors: Wang Juyi and Elise Mak.

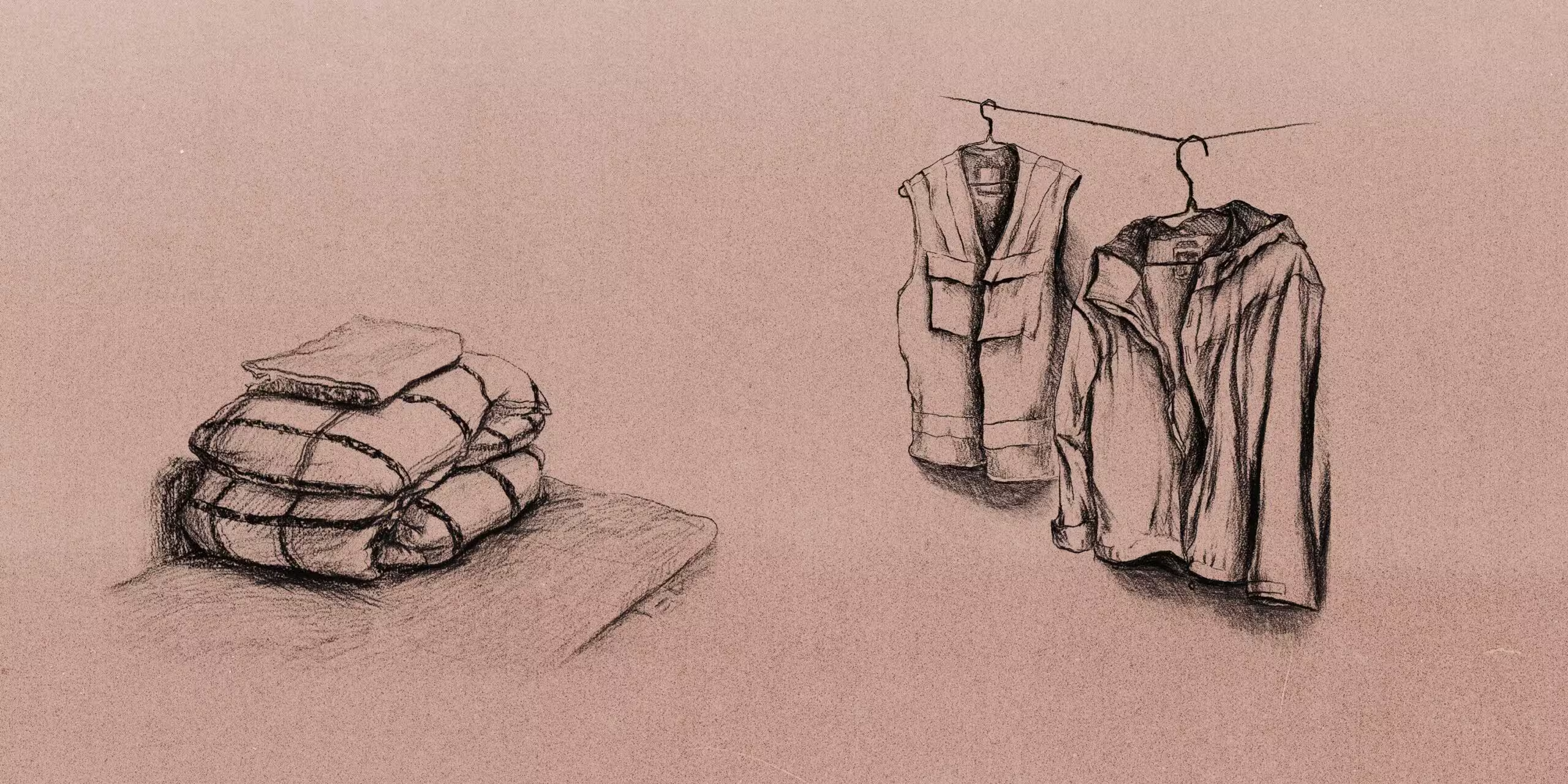

(Header image: Visuals from Insight Media, reedited by Sixth Tone)

Comments

This site uses User Verification plugin to reduce spam. See how your comment data is processed.